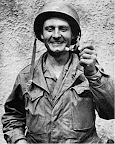

Fr. Emil Kapaun

Fr. Emil Kapaun

The following Sunday, Fr. Kapaun collapsed. His condition was serious – a blood clot, severe veinal inflammation, malnutrition – but the Chinese guards in the North Korean prison camp would allow no medical treatment, not even painkillers. After languishing for several weeks, he died on May 23 and was buried in a mass grave.

Emil Kapaun was born on April 16, 1916 to a poor, but faith-filled farm family on the prairies of eastern Kansas. Life was hard and even children had to learn to be resourceful as mechanics and carpenters and to care for the animals during bitter winters and brutally hot summers. With a strong desire to become a priest, he attended Benedictine Conception Abbey to complete high school and college, continued his studies at Kenrick Seminary in St. Louis, and was ordained in 1940.

In 1944, Fr. Kapaun enlisted as a chaplain in the U.S. Army, and served for two years in Burma and India, before returning to civilian life. Two years later, he reenlisted and was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division in Japan.

In June 1950, a North Korean army crossed the 38th parallel, and advanced quickly toward Seoul, South Korea. The U.S. intervened militarily, with the 1st Cavalry Division executing an amphibious landing to block the advancing army. The enemy onslaught was severe and the U.S. units soon were in retreat. The fighting was intense. Fr. Kapaun, with his soldier-parishioners in danger, was tireless. He moved among the GIs, ignoring enemy fire, comforting the wounded, easing fears, administering the last rites, burying the dead, and offering Mass whenever and wherever he could. On one occasion, he went in front of the U.S. lines, in spite of intense fire, to rescue a wounded soldier.

On September 15, 1950, the war took a radical turn when U.S. troops landed at Inchon behind the invading army. The North Korean forces fled northward, with the Americans in pursuit. Within a few weeks, the 1st Cavalry Division had crossed the 38th parallel. Unknown to them, China had secretly moved a huge army into North Korea.

The night of November 1 was quiet. Kapaun’s battalion, which had suffered some 400 casualties among its roster of 700 soldiers, was placed in a reserve position. Chinese troops, however, had infiltrated to within a short distance of them. Suddenly, just before midnight, there was a cacophony of bugles, horns and whistles, as the enemy attacked from all sides.

Fr. Kapaun scrambled among foxholes, sharing a prayer with one soldier, saying a comforting word to another. He assembled many wounded in an abandoned log dugout. All the next day, he scanned the battlefield and, some 15 times, when he spotted a wounded soldier would crawl out and drag the man back to the battalion’s position. By day’s end, the defensive perimeter was drawn so tightly that the log hut and the wounded it contained were outside of it. As evening came and another attack was imminent, the chaplain left the main force for the shelter so that he could be with the wounded. It was soon overrun, and Fr. Kapaun pleaded for the safety of the injured. Approximately three-quarters of the men in the battalion had been killed or captured.

Hundreds of U.S. prisoners were marched northward over snow-covered crests. Whenever the column paused, Fr. Kapaun hurried up and down the line, encouraging the men to pray, exhorting them not to give up. When a man had to be carried or be left to die, Fr. Kapaun, although suffering from frostbite himself, set the example by helping to carry a makeshift stretcher. Finally, they reached their destination, a frigid, mountainous area near the Chinese border. The poorly dressed prisoners were given so little to eat that they were starving to death.

For the men to survive they would have to steal food from their captors. So, praying to St. Dismas, the “Good Thief,” Fr. Kapaun would sneak out of his hut in the middle of the night, often coming back with a sack of grain, potatoes or corn. He volunteered for details to gather wood because the route passed the compound where the enlisted men were kept, and he could encourage them with a prayer, and sometimes slip out of line to visit the sick and wounded. He also undertook tasks that repulsed others, such as cleaning latrines and washing the soiled clothing of men with dysentery.

Fr. Kapaun’s faith never wavered. While he was willing to forgive the failings of prisoners toward their captors, he allowed no leeway in regard to the doctrines of the church. He continually reminded prisoners to pray, assuring them that in spite of their difficulties, our Lord would take care of them. As a result of his example, some 15 of his fellow prisoners converted to the Catholic Faith.

Fr. Kapaun’s practice of sharing his meager rations with others who were weaker, lowered his resistance to disease, and eventually to his death. For his heroic behavior, he received many posthumous honors, including the Distinguished Service Cross and Legion of Merit, had buildings, chapels, a high school, and several Knights of Columbus councils named in his honor, and will be awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously in April 2013. In 1993, the Pope declared Fr. Kapaun a “Servant of God,” and his cause for canonization is pending.