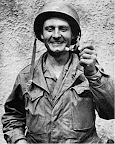

Fr. Francis Duffy

Fr. Francis Duffy

The center of the American position, south of the river, was Villers-sur-Fere, a small village about a thousand yards from the enemy position. At its north end was a large church square, on which bordered a schoolhouse which was being used as a hospital. The square, in sight of the enemy, was a hub of activity, and so was frequently shelled and raked by machine gun fire. A narrow street leading to the square was aptly named Dead Man’s Curve.

The Americans faced German air superiority and a determined, battle-seasoned enemy who was heavily armed and well-positioned. For four days of fierce fighting, the American continued the attack. They prevailed, driving the Germans farther north, but at a fearful price. The Division had been reduced to half of its combat strength. Of the over 5,600 American casualties, one-third occurred in or around Villers-Sur-Fere.

A calming presence as the battle raged was Fr. Francis Duffy, the Division’s senior chaplain. Father was always near the heaviest fighting, exposing himself to constant danger as he moved from unit to unit, carrying the wounded, comforting the dying, and relaxing tensions as he used his Irish wit in chatting or joking with soldiers. His effect on the morale of the troops was enlivening, much more so than that of a typical cleric. Colonel Douglas MacArthur, chief-of-staff of the 42nd Division, even thought of appointing him regimental commander, an unheard of position for a chaplain.

For his valor in this engagement, Fr. Duffy was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. General John Pershing, commanding the American troops, said that “despite constant and severe bombardment with shells and aerial bombs, he continued to circulate in and about the two aid stations and hospitals, creating an atmosphere of cheerfulness and confidence by his courageous and inspiring example.”

Francis Patrick Duffy was born in Ontario, Canada, in 1871 and emigrated to New York, where he was ordained a priest in 1896. Two years later, while engaged in graduate studies at The Catholic University of America, the United States entered the war against Spain over Cuba’s independence. He volunteered as an Army chaplain, but was not sent overseas. Completing a doctorate, Fr. Duffy joined the faculty at St. Joseph’s Seminary, Dunwoodie, in New York, where a student of his was Francis Patrick O’Boyle.

In 1912, Fr. Duffy was assigned as the founding pastor of Our Savior Parish in the Bronx. Shortly thereafter, he also assumed the duties as chaplain of the “Fighting Sixty-Ninth,” an Irish regiment of the New York National Guard. With America’s entry into World War I, the regiment was mobilized as the 165th Infantry Regiment and assigned to the newly established 42nd Division, known as the Rainbow Division as it was composed of National Guard units from 26 states.

As the Division sailed for France, the poet Joyce Kilmer, one of its members who was killed at the battle of the Ourcq, wrote that every morning, Father Duffy would offer Mass to a large crowd on the main deck. And every afternoon and evening, there would be a queue of soldiers “as long as the mess line” waiting for Father to hear their confessions. Throughout the war, as the unit fought in the Lunéville sector, the Baccarat sector, the Champaign sector, at the Ourcq, the St. Mihiel offensive, and the Argonne-Meuse offensive, a total of 180 days in combat, Fr. Duffy continued to minister to the spiritual, physical and emotional needs of the men. For this, he was highly beloved by the men and became a legendary figure.

A year after he received the Distinguished Service Cross, a combat award, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, a non-combat distinction, for his fearless and tireless devotion to duty and his inspirational leadership in the trenches and behind the lines. He also received New York State’s Conspicuous Service Cross, France’s Légion d’honneur, and the Croix de Guerre, making him the most highly decorated chaplain in the history of the U.S. Army.

After the war, Fr. Duffy returned to New York, and became pastor of Holy Cross Church, a few blocks from Times Square. In 1927, when Al Smith was running for president, Protestants were apprehensive that a Catholic with his allegiance to the Pope could not be loyal to the Constitution. Fr. Duffy ghostwrote a piece for Smith on Catholic American patriotism, in which he discussed aspects of religious freedom and freedom of conscience that were later reflected in the Declaration on Religious Freedom, issued by the Second Vatican Council.

When Father died in 1932, his requiem Mass was held in St. Patrick’s Cathedral to an overflow crowd estimated to be 25,000 mourners. He received full military honors, with his coffin carried on a caisson and accompanied by his riderless horse with his boots in reversed stirrups. Thousands of people from all walks of life accompanied his body from the cathedral to its final resting place in the Bronx. Later a statue of Father in his World War I uniform was placed on the north side of Times Square, an area now known as Duffy’s Square.