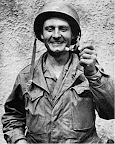

Fr. Joseph O’Callahan, S.J.

Fr. Joseph O’Callahan, S.J.

3-ocallahan-profile.png

https://picasaweb.google.com/117767622145930935372/AWDPatriots#5850581270354727122

3-ocallahan-ministering.png

https://picasaweb.google.com/117767622145930935372/AWDPatriots#5850581270769466978

Joseph Timothy O’Callahan was born on May 14, 1905, in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Upon graduating from high school, he joined the Jesuits and was ordained in 1934. For the next six years, he taught mathematics, physics and philosophy at several of the Order’s colleges.

In August 1940, with war raging in Europe, Fr. O’Callahan enlisted in the Naval Reserve Chaplains Corps. Several assignments followed before he reported on March 2, 1945 to the aircraft carrier USS Franklin, to serve as chaplain to its 3,200 men. The ship was part of a task force whose mission was to track down the Japanese fleet and destroy it.

On March 18, with the U.S. ships about 100 miles from Japan, American planes took off in waves beginning at first light. Their role was to engage and destroy the Japanese air power, and then locate the enemy vessels which were scattered throughout inland waters. Before each flight, Fr. O’Callahan visited the various pilot ready rooms, praying with the men and giving them general absolution. The U.S. pilots dominated the skies, but did not locate the enemy ships until just before dark. The strike against them would have to wait until the next morning.

March 19 began as the day before. The first wave of planes left the carrier at 5:30 AM. Shortly afterwards, as the second wave was being readied, with full tanks of fuel and loads of rockets and bombs, a Japanese plane evaded the American air cover. It flew over the Franklin releasing a bomb that penetrated the flight and gallery decks and exploded on the hangar. Within seconds, gasoline ignited and a wave of searing flame raced down the three football-field length of the hangar, gaining impetus as it proceeded from exploding planes. Some 800 men were dead.

Fr. O’Callahan retrieved a vile of holy oil and his helmet marked with a large white cross as he made his way through passages filled with flames and smoke to the open area above. On the hangar deck, bombs and rockets, engulfed in a mass of flames, were exploding at a rate of about one per minute.

Father continued upward to the flight deck. Here nearly 90 percent of the 1,000-foot apron was aflame. The clear portion was full of burned, mangled, bleeding bodies. He spent a few moments with each of those who were alive, praying, absolving, anointing. Explosions tore apart the steam lines and the boilers shut down. By 9:30 AM, the ship was powerless and listing. Twenty minutes later, a rear service magazine of five-inch shells exploded, raining debris onto the deck.

The fury brought disorganization. Key officers were dead, and many chiefs, if alive, were dispersed or trapped. Flames, explosions and noxious smoke smeared faces and uniforms making it almost impossible to recognize anyone from a distance. One thing stood out, however, the white cross on the chaplain’s helmet. It had the power to inspire.

Depleted hose crews needed help. Father rallied a group of men to join him on the hoses. When the fire marshal entered smoke-filled portions of the ship looking for breather masks, the priest was with him. When a live, thousand-pound bomb was spotted on the deck, the chaplain stood by for moral support while a team defused it; then he mustered a group of men to drop it overboard. When the fires were pushed back from the forward gun turret and its ready-ammunition magazine, hundreds of five-inch shells stored there had to be jettisoned before they exploded. Fr. O’Callahan had men form a chain, taking his turn in the line, to pass the hot shells from the magazine to the edge of the ship where they were dumped. He then joined a crew to flood a lower-deck magazine whose ammunition could not be easily unloaded.

When the fires on the hangar deck began to subside, Father led a hose crew through a smoke-filled, dark passage to the area. On the flight deck, as the fires receded, six loose, but live, thousand-pound bombs were discovered. The chaplain was there encouraging the men as a hose crew worked to cool the bombs so others could defuse them.

That evening, the engineers were able to return to their stations, and by 9 AM on the 20th, the Franklin was moving under its own power. Burial parties were formed to take care of the hundreds of dead. All day and night, the priest and the Protestant chaplain held a brief prayer service for each man as he was assigned to the sea. On April 3, one month after it left, the ship, entered Pearl Harbor. For his courageous acts, Fr. O’Callahan was awarded the Medal of Honor, the first chaplain since the Civil War to be so honored.

Released from active duty in November 1946, Father O’Callahan returned to Holy Cross College as a professor of philosophy. He died in Worcester on March 18, 1964, the eve of the nineteenth anniversary of his heroic acts.